THE HISTORY OF THE STONES – FROM RESPECT TO NEGLECT TO RECLAMATION

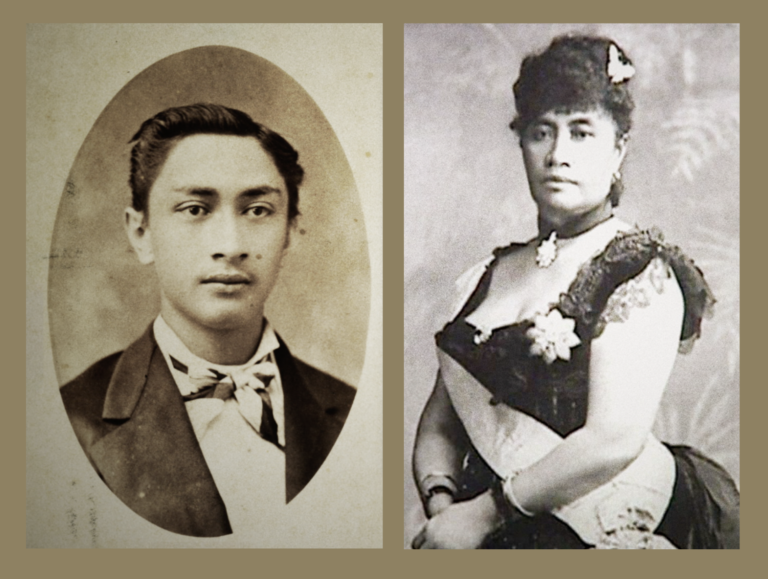

Princess Kaiulani

After the healers left Hawaii, the stones remained in Waikiki for centuries and were revered by Hawaiian nobility. One of the stones was partially exposed on the beachfront property of Princess Likelike and her daughter Kaiulani, the sister and niece of Queen Liliuokalani, who prayed and placed seaweed lei on them before bathing in the sea.

Aalapuna Boyd and Queen Liliuokalani

Their devotion led Likelike’s husband, Governor Archibald Scott Cleghorn, to excavate the four stones in 1905, and his son-in-law, James Aalapuna Harbottle Boyd, to convey their story to the publisher of the Hawaiian Almanac. Cleghorn so respected the stones that he stipulated in his will that they “shall not be defaced or removed” from his premises.

The stones were buried under this bowling alley for 22 years.

But colonization and the introduction of foreign religion led to neglect of the stones, and disrespect for mahu, and in 1941 the stones were buried under a bowling alley.

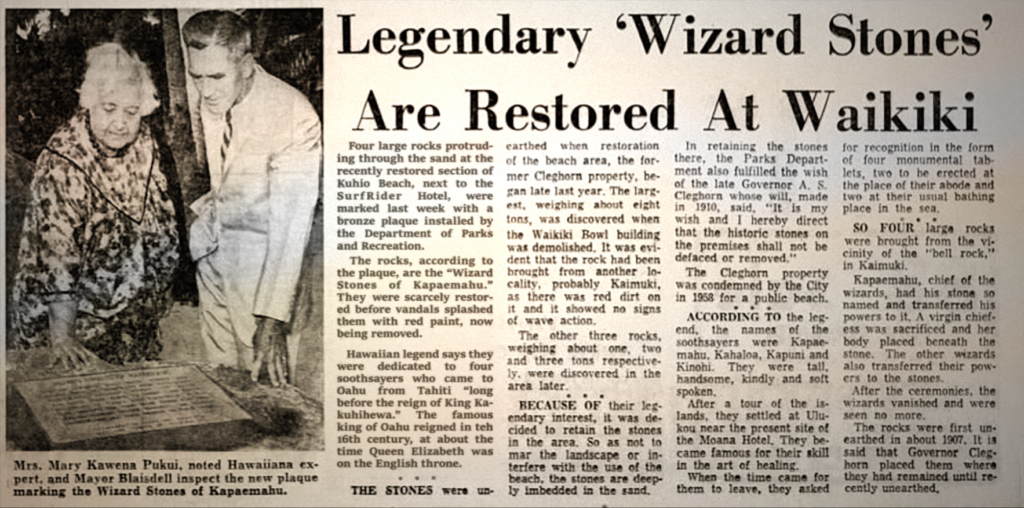

Mary Kawena Pukui and Mayor Blaisdell

The stones were recovered in 1963. Fortunately, preeminent Hawaiian authority Mary Kawena Pukui knew the story of the stones, which she defined as “a row of mahu,” and insisted they be preserved.

Pukui believed that the mahu healers were “respected men; talented priests of healing and of the hula. Whether this is history or legend, it reflects attitudes of approval and admiration.”

Tahitian stone

The Department of Parks and Recreation embedded the stones on the beach, where they were often used by people to dry their towels and sunbathe. In 1980, they were moved about 50 feet mauka to make way for a new restroom, and were set off inside a circular paved enclosure.

In 1997, as part of an effort to restore Hawaiianness to Waikiki, a major restoration was undertaken. The stones were placed on an elevated platform surrounded by a fence, plants of medicinal value were added to the site, and a small stone thought to come from the healers’ home in Tahiti was brought from Raiatea and placed on a stone altar.

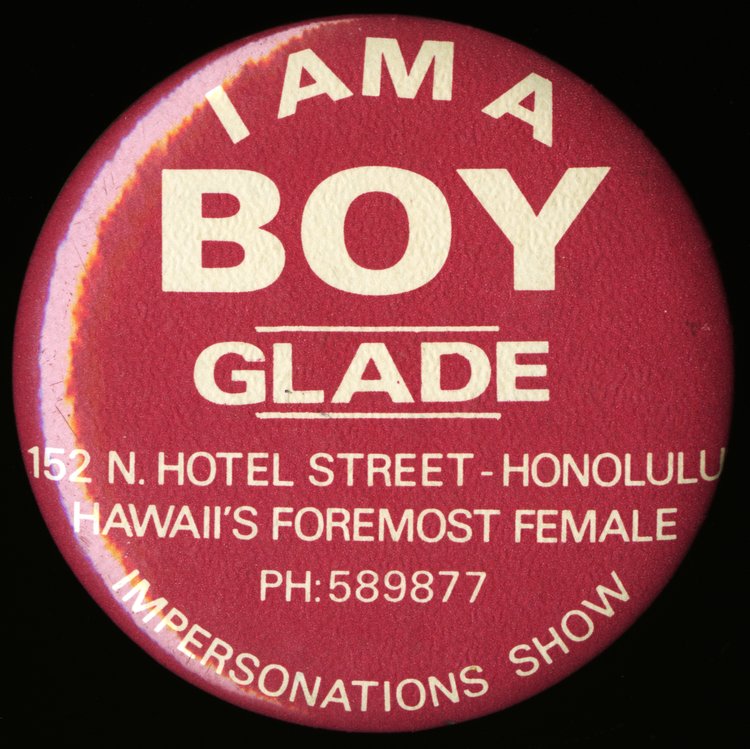

Button worn by Mahu entertainers

The informational plaques accompanying these different iterations of the monument made no mention that the healers were mahu, nor that their dual male and female spirit was central to their abilities and accomplishments, reflecting the strong anti-mahu climate that was pervasive during this time period. For example in 1963, Hawaii passed a law that necessitated mahu nightclub entertainers to wear a button proclaiming their biological sex to avoid arrest. In the 1990s, the issues of HIV and same-sex marriage became prominent, eliciting a strong backlash against all gender and sexual minorities. “Everybody knew they [the healers] were mahu, but you could never say that” said a Waikiki elder. “They would have destroyed the stones! That’s why we kept it so hush-hush.”

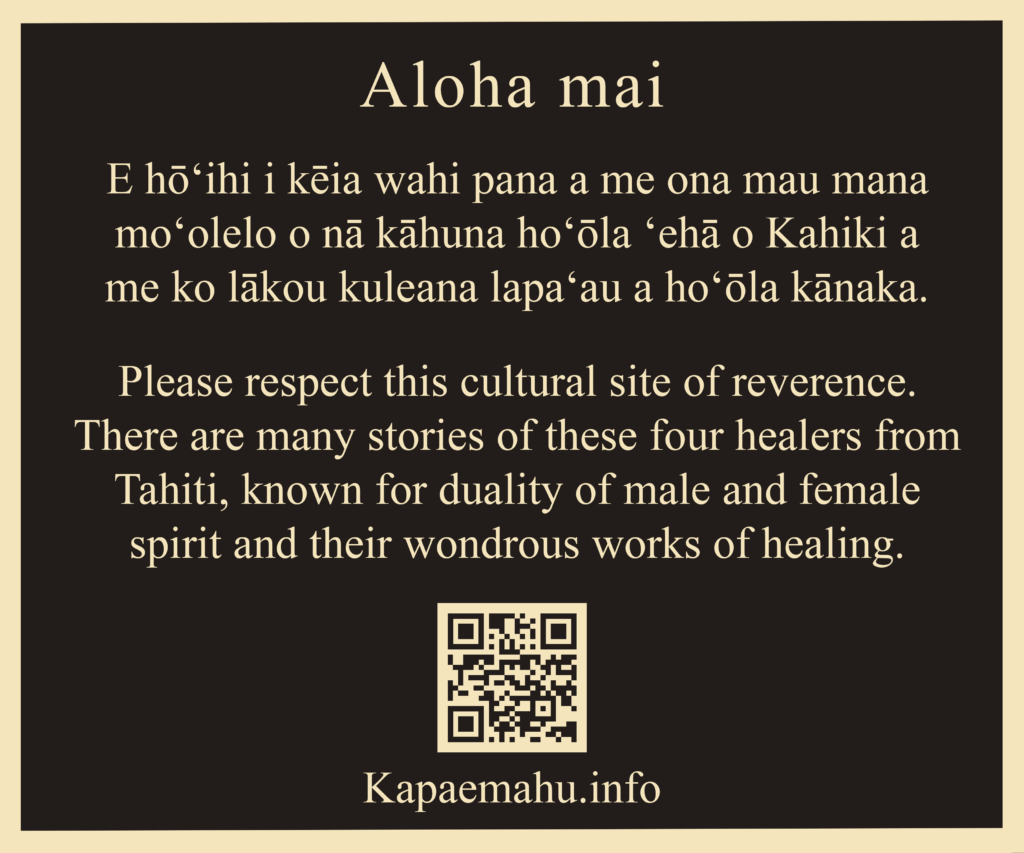

New site marker

Beginning a decade ago, a movement grew to restore the once-honorable status of mahu as respected members of society with important responsibilities as caretakers, healers, and keepers of ancient traditions. As part of this effort, the multimedia eduction and engagement collective Qwaves Kanaka Pakipika uncovered and made known new information and understandings of Kapaemahu that stimulated a community-based effort to update the signage at the site. In 2023, a new bronze plaque was installed on a stone in front of the site to provide visitors and residents with information to help them better understand the history, stories, and current meanings of this ancident wahi pana.

Hawaii LGBT Legacy Foundation Indigenous Committee honors the stones

Today the stones occupy a protected location in the heart of Waikiki beach. For those who know their history and understand their meaning, they are a permanent reminder of the skills and accomplishments of the four mahu healers. You can help preserve the honor and dignity of this storied site by sharing their story.